Keith Alexander Lee

I’ll never forget my childhood trips to the Florida Keys during the 1970s. Growing up in Ontario, Canada, these vacations were a delightful escape from the frigid winters, introducing me to experiences that were quite different from those on the Great Lakes. This was a time when savoring local conch and indulging in all-you-can-eat shrimp straight from the Gulf was a cherished part of our adventures.

One day, I convinced my parents to make a stop at a marina in Islamorada after the charter boats returned. Unlike others who sought out grouper or snapper, I had one thing in mind: to see sharks up close. Until that moment, my only encounters with these fascinating creatures had been through shows like The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and National Geographic. That day was unforgettable, but not for the reasons I expected. Instead of lively sharks, I found a grim scene. Various sharks, including impressive tiger and great hammerhead varieties, were hanging lifeless by their tails, their fearsome teeth starkly exposed as their heads rested on the ground. It’s an image that has remained vivid in my memory.

Fast forward a few decades, and as I navigated my undergraduate studies, I began to grasp the intricate relationships between different fish species and their habitats. A textbook staple was the depiction of an ocean food web, showcasing a shark perched at the top, alongside narratives that elucidated the pivotal role apex predators play in fostering and maintaining a balanced ecosystem. Unfortunately, this was during a period when the pressures exerted on ocean ecosystems were intensifying. As Sandy Moret, a renowned tarpon angler from the Florida Keys, put it, our oceans were feeling “the weight of humanity.”

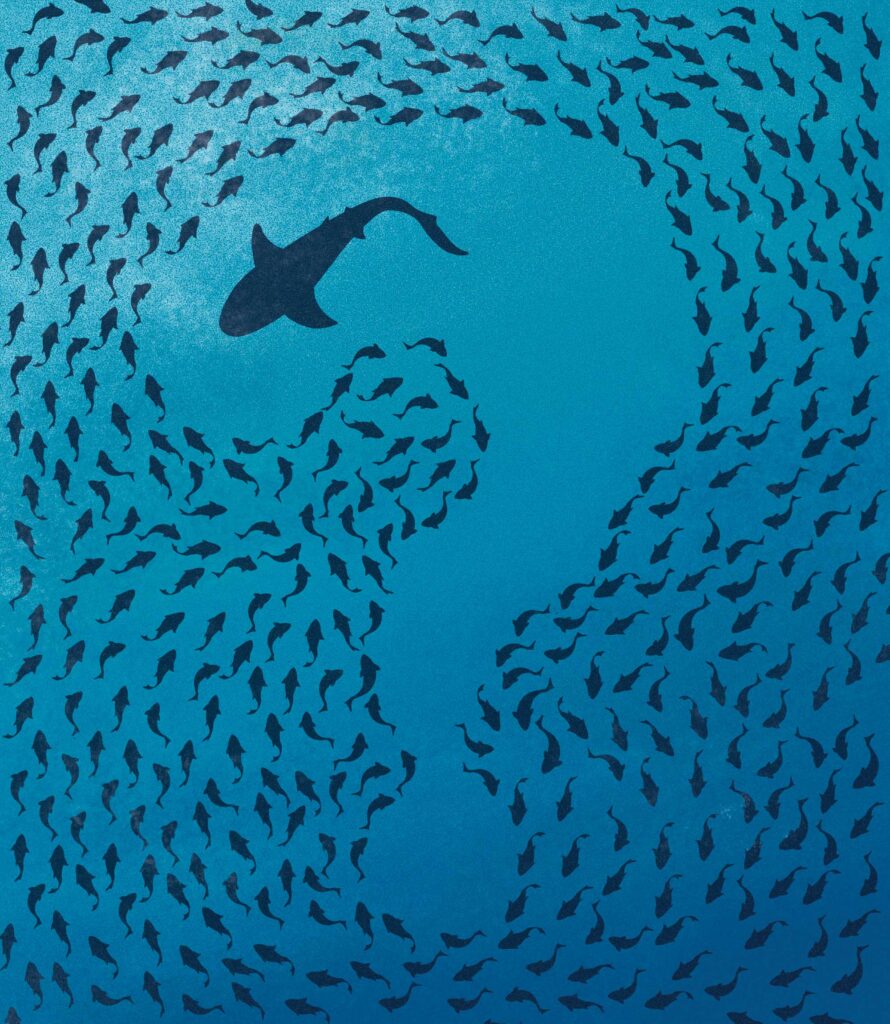

By the late 1990s, the overexploitation of sharks for commercial gain had escalated to alarming levels, rendering numerous species vulnerable, threatened, and even critically endangered. Media outlets began highlighting the severe implications of shark finning, underscoring a stark reality: without sharks, our ocean ecosystems were destined to spiral out of balance.

This initiated a wave of national and international shark conservation efforts. After three decades of dedicated work, we’ve made some strides; however, a significant number of species are only just beginning to show signs of recovery. Sadly, the global shark populations still predominantly trend downward.

Now, here’s where things get complicated. As some shark species start to rebound, fishermen are reporting an uptick in the frustrating experience of losing hooked fish to these predators. This phenomenon is known as depredation. What’s more, the number of fishermen casting lines in our coastal waters is at an all-time high, leading to even more frequent encounters with sharks. While fishing remains a beloved pastime and anglers play a crucial role in observing and promoting conservation, the moment a shark snatches a prized fish from your line, it can be incredibly frustrating. Even for those fish we release, the threat of predation persists once they swim away.

So, is the issue really about sharks? My research team at UMass has been investigating depredation and post-release mortality in recreational fisheries for several years now. The tension between anglers and sharks is only growing. We’re also seeing other predators, such as sea lions in Pacific waters, joining the mix. Reflecting on my childhood visits to the Keys, I can vividly recall the day I witnessed a gigantic great hammerhead shark chase down a tarpon right beneath the Bahia Honda Bridge. This dramatic encounter unfolded as we attempted to land a tarpon for tagging purposes to study their movement patterns. Engaging with local fishing guides and fellow anglers sparked our interest in researching the factors contributing to the likelihood of a hooked tarpon getting seized by a great hammerhead.

Read Next: Are Mako Sharks Dangerous?

Our findings indicated that fight time and tidal conditions were crucial variables. The longer an angler fought a tarpon on the line, the higher the probability of depredation. Furthermore, there was notable overlap in the habitats frequented by tarpon and great hammerheads during outgoing tides, amplifying the likelihood of encounters as anglers engaged their catches.

Who among us doesn’t revel in the thrill of battling a fish on rod and reel? However, for the schools of tarpon gathering beneath the bridge before spawning, an extended fight could sometimes lead to a death sentence. Losing these spawners holds significant implications for the future generations of tarpon. Thankfully, there’s a straightforward solution to address the first part of this dilemma: fight tarpon with more intensity and aim to land and release them in under 10 minutes. Naturally, a shark might still pursue the fish after release, but at least the tarpon stands a better chance of survival.

Over the past five years, reports of depredation incidents involving sharks have surged on social media and the internet. Recently, my lab conducted a survey of anglers fishing between North Carolina and Maine. Preliminary results indicate that depredation isn’t solely a shark issue, with seals and seabirds also snatching anglers’ catches. There’s clear frustration and concern surrounding these incidents, particularly regarding safety when reaching down to the water to land a fish.

In response to these growing challenges, the House of Representatives recently passed the SHARKED Act to allocate federal funds aimed at finding solutions. Fishing is not only a cherished leisure activity that drives passion and supports the economy; it’s also essential to the health of coastal ecosystems, a role played by sharks and other predators. There’s still a lot of work ahead of us to resolve this complex issue.