Many might argue that catamarans are not suitable for the UK waters. If concerns about high sides, wide beams, marina costs, or the myth that they don’t perform well upwind have deterred you, read on. The Excess 11 has certainly changed my perspective.

High-volume production catamarans are ideal for family charters in warmer climates and easing novices into life on the water, yet I was curious if a newer catamaran brand could also serve as a truly practical and enjoyable cruising vessel for private owners in the UK’s cooler seas.

The cruising catamaran market has recently forced buyers to choose between either a high-volume, stubby-keeled type or a speedy dagger-board model. However, alongside Nautitech, Excess has entered a niche for high-volume, yet modestly-displaced cruising cats, aiming to provide the perfect balance of both styles.

Theo discovered that the Excess 11 is robust and features an impressive finish. Photo: Paul Wyeth

The Excess brand was launched by the Beneteau Group just six years ago to fill this gap in the market. With top racing catamaran and IMOCA foiling designers VPLP involved, this boat has performance embedded in its design. Could this catamaran be comfortable for living, sturdy at sea, and genuinely fun to sail?

At first glance, the Excess 11 shares characteristics with other modern cruising cats—tall topsides, a large glass-walled deck saloon, ample hull space, and shallow, long-keel designs. However, it was its unique features that caught my attention. Firstly, at just 37ft in length, it is a full 3ft shorter than its closest competitors, with only the Broadblue 345 being smaller.

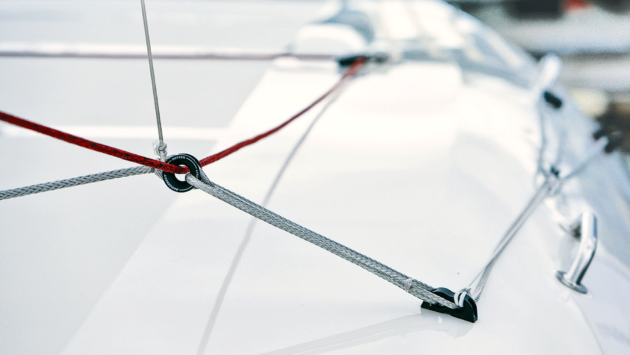

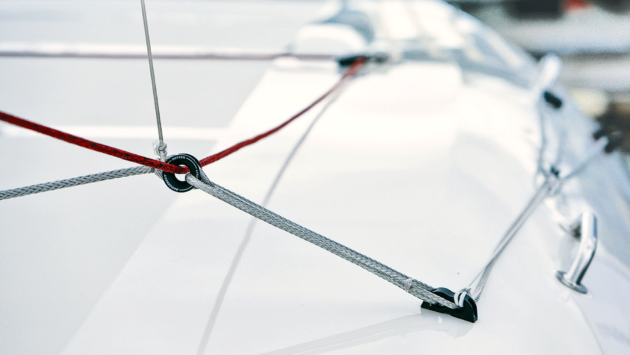

Instead of a single raised helm, the Excess 11 has two helm stations located on the main deck, positioned at the rear and outside the superstructure. To enhance the steering experience, it utilizes Dyneema cables as opposed to hydraulics; with the wheels in their current positions, this results in an impressively short cable run that minimizes play and maximizes feedback.

Sheeting angles are managed by in-and-out haulers for the overlapping genoa. Photo: Paul Wyeth

Winches are located at deck level, allowing more crew involvement, and it presents a surprisingly competitive price when compared to monohulls. While the Excess 11’s base cost might exceed that of similar-sized boats, obtaining the same space aboard would require considering vessels at least five to ten feet longer.

This led me to navigate the Hamble River, gripping the bright orange helm of an Excess 11. With the steering wheels situated right at the back and outboard, a clear view forward and to the sides is readily available. Through the glazing, one can still view beyond the saloon’s curves.

A slight adjustment inboard, while still reachable from the wheel, provides visibility around the support posts and directly ahead. It takes a moment to acclimate, as the tops of the windows fall slightly below eye level (I stand at 6ft 1in), but it’s akin to steering a deck-saloon monohull or simply leaning to the side to peek around a headsail.

The boom is low enough that stowing the sail is easy from the coach roof. Photo: Paul Wyeth

Command and Control on the Excess 11

While we cruised, I appreciated the ability to control the boat from either side using electronic throttles connected to the twin 29hp Yanmar engines; this allows steering from either helm station.

Although catamarans are generally stable, you may notice there’s no prop wash on the rudders, which is typical among many cats. This is because the rudders are positioned ahead of the propellers, allowing the engines to be pushed back, thereby saving cabin space. This setup means you can maneuver the catamaran using the throttles much like driving a tank—though I can’t personally attest to that.

The conditions weren’t sunny—clouds seemed to stubbornly shade the sky and temperatures were unexpectedly low for summertime—but we enjoyed a decent breeze. As expected from a multihull, the main sail is large and powerful to propel the twin hulls, and a two-to-one halyard connected to the powered winch near the starboard helm helped us set it up.

The dramatic hull flares become evident from the bow view. Photo: Paul Wyeth

On our test model, the Excess 11 from Sea Ventures, nearly all lines except a few halyards were directed back to clutches and a winch located near the starboard wheel, including both sheets for the overlapping jib. Most owners prefer to choose the self-tacking jib, making it even simpler.

Having all controls on one side leads to a significant amount of rope gathered in one area, which needs to be organized, though I imagine dividing them between both sides might make some of them frustratingly out of reach for the helm.

As we set sail, we began a beat out of Southampton Water and around Bramble Bank into open seas. Before I could remind myself that multihulls are not designed for graceful tacking, I put her into a tack just as I would with a monohull; she transitioned through easily and took off almost immediately.

For a family cruiser, a catamaran is a smart choice. Photo: Paul Wyeth

A gentle bear away restored any lost speed, allowing us to point up to 40º-43º off apparent wind, resulting in compass tacking angles of 115º-120º—not bad for a cruising cat. Given we were sailing over 7 knots upwind in a Force 4 with this 37-footer on an even keel, that’s quite impressive and likely nearly a knot faster than what you’d achieve in a similar-sized monohull. Of course, in larger swells, the additional hull and possible slamming from the nacelle might reduce this speed, but the Solent’s chop was insufficient to test that.

Article continues below…

The multihull market is clearly thriving. Their appeal as charter vessels has been established for years, mainly due to the amount of space…

Helming Experience

Sailing from the windward helm, I appreciated being positioned outboard, allowing me to see forward and feel the wind. The helm was light and responsive; although you miss the feedback of heel and load, it was sensitive enough for me to gauge the sail balance—an experience not often found in heavier cruising cats. Observing the genoa telltales was a bit tricky, so steering from the leeward side helped with visibility.

The starboard wheel houses most controls, yet throttles can operate from either side. Photo: Paul Wyeth

In terms of visibility, it was arguably better than sailing to windward in a monohull, as the sails sit above the line of sight from the hull, and the saloon windows allow clear viewing.

As we bore away and the wind picked up, we accelerated to 7.5 knots on a close reach, but true speed was achieved by deploying the 54m2 Code Zero, which was easily set and furled using the foldable bowsprit (this pivots back to reduce length in harbor). We consistently maintained speeds above 8 knots, occasionally hitting high nines, with a top speed of 10.1 knots as the wind reached the Code Zero’s maximum recommended range. The large asymmetric sail is perfect for lighter winds and broader angles.

The modest galley and chart table are sufficient for cruising with a partner or a few friends. Photo: Paul Wyeth

The sail plan’s crossover table indicating recommended wind ranges for each sail option proved very beneficial; sailing a catamaran with no heel angle necessitates a more numerical approach. While seasoned owners might improvise, this boat feels like it can confidently handle its sails. While not designed for planing, she is capable of surfing in double-digit speeds.

Handling the Code Zero was straightforward—only the headsail halyards were directed to port, along with the furling line for the Zero, while sheets go to the winches on either side, meaning a couple of crew members are needed to release and trim after a gybe. Furling the sail may be easier for gybing, but managing the winches is manageable from the helm. If you desire two winches, however, you’ll need to consider the larger Excess 14.

You can achieve good cruising speeds with minimal hassle. Photo: Paul Wyeth

The advantage of having both wheels and lines stationed on deck level with the cockpit is that crew can easily assist, enhancing involvement and improving communication. This setup also feels more secure in rough water, while being closer to the water enhances the sailing experience.

The seats fold down behind the helm across the stern access, providing comfortable seating for two people and enhancing security at the wheel, a factor supported by the high bulwarks. Steps found inboard of the wheels lead up to the spacious side decks.

On the foredeck, much of the area is designed as a trampoline to keep weights and potential slamming toward the rear. The anchor mounts onto a bow roller adjacent to the forestay, with the chain led aft to spacious nacelle lockers situated in front of the saloon windows via a molded channel, keeping the chain flush underfoot. Most owners will likely choose a second 300-liter water tank in this locker, as there’s ample room, allowing for a more relaxed approach to water management.

The saloon nav station adds practical workspace, though it’s too small for a chart. Photo: Paul Wyeth

All accommodation hatches are flush with the deck, and each bow is equipped with a spacious fo’c’sle locker for additional gear and sails. There’s an option to convert these lockers into extra berths for those desiring accommodation for up to twelve on board.

The Sociable Cockpit of the Excess 11

The onboard living arrangements of the Excess 11 are quite practical, particularly for a crew of six using the three-cabin layout that most owners prefer. We noted that the crew tends to gather at the rear of the cockpit, which features six seats across the stern, a bench seat to port, and an L-shaped seat around the cockpit table, providing ample space to relax.

A hard-top canopy effectively shields the cockpit from sun and weather. Photo: Paul Wyeth

The low boom allows for sail packing at waist height from the canopy, eliminating the need for climbing, prompting many owners to choose a hard-top cockpit canopy that can also support solar panels. A folding canvas ‘targa’ top is also available for those wanting to increase light exposure.

Walking forward through the sliding doors, you emerge into a spacious area around the saloon table, surrounded by an L-shaped settee against the forward bulkhead, and a couple of stools for additional seating. The starboard end features a nav station, though navigation is generally done on deck.

To the starboard side’s aft and outboard, you find the L-shaped galley, equipped with a fixed oven and two-burner gas stove, front-opening fridge, and several lockers. To the port of the entrance, additional large lockers are perfect for stowing life jackets and sailing gear, or extra food supplies, with some storage available under the saloon seats. While it’s not the largest galley, it is essential to remember that this boat measures just 37ft. It’s adequate for week-long cruises or longer trips for a couple.

Ample space and natural light create a welcoming saloon environment, both at the dock and while sailing. Photo: Paul Wyeth

It’s within the hulls that one truly appreciates the benefit of their volume. A distinct flare above the waterline maximizes space without increasing drag, while resulting chines help minimize spray. Thoughtful contours in the topsides also lessen the visual mass of the flat sides while boosting strength and space.

On the port side, you’ll find comfortable double cabins at both ends, each equipped with almost square berths and a well-sized head with a separate shower compartment in between. Both cabins have a sizeable hull window with an opening port and ceiling hatch, along with storage lockers and under-bed compartments.

However, the selling point is in the starboard hull. How many 37-footers provide almost the entire length for a single cabin? The owner’s suite can be closed off from the boat’s other areas with a sliding door at the stairway. There’s a locker and a desk/dressing table at the base of the three steps, a spacious double berth at the back, while the front section features a large bathroom—unlike the typical cramped heads—with its own shower compartment and additional lockers.

Generous space for the owner’s cabin, courtesy of the entire hull being for personal use. Photo: Paul Wyeth

The Resilience of the Excess 11

In terms of upkeep, very little requires access beyond the heads seacocks situated in the main hulls. Most systems are located in the sizable engine compartments just behind the wheels, accessible via deck panels that hinge backward for easy access without needing to balance on the bathing platform.

Overall access is commendable, though the engines are installed with the sail drives positioned out back, resulting in the alternator, impeller, and water strainer being situated far forward with no direct approach. The manufacturer pointed out that if the engines were flipped, with the sail drives nearer to the rudders, it would negatively impact the efficiency of both the rudder and propeller, although this is acknowledged as a trade-off.

Aft-hinged engine bay hatches provide excellent access to the rear end of the engine and most onboard systems. Photo: Paul Wyeth

Another potential concern is that the Dyneema steering cables, which I found pleasing at the helm, run directly above the engine. Although HMPE rope’s melting point is 150ºC, its maximum operating temperature is reportedly 70ºC, while certain engines might operate beyond 80ºC under standard conditions.

In the case of an engine fire, it is possible to damage the steering cable; yet the alternative wheel should still allow control of both rudders via a tie bar, or, if necessary, the emergency tiller offers a backup. Other than this, the boat’s finishing impressed me with its high standard and absence of rough edges.

Structurally, the Excess 11 has been built to be quite robust. Since a catamaran doesn’t require ballast, all weight can be committed to its structural integrity. The keels feature reinforced ‘shoes’ of extra GRP to handle vertical loads, enabling the boat to sit comfortably on them. These are molded as part of the hull, filled with foam, and capped with laminate before the complete structure undergoes vacuum infusion with resin.

Most owners will prefer the larger Pulse Line sailplan together with the simpler self-tacking jib. Photo: Paul Wyeth

There are no keel bolts to concern yourself with; however, they are designed so that in the event of a substantial side impact to the keels, they would fail without compromising the watertight integrity of the hull, serving as a fuse that allows the boat to continue sailing until repairs can be made—this seems quite sensible to me.

Guests are not shortchanged either, with extensive sleeping places and views from the hull windows. Photo: Paul Wyeth

Specifications of the Excess 11:

LOA: 11.42m / 37ft 6in

Hull length: 11.33m / 37ft 2in

Beam: 6.59m / 21ft 7in

Draught: 1.15m / 21ft 7in

Displacement: 9,000kg / 19,845 lb

Sail area: 77m2 / 829 sq ft (Pulse line 82m2 / 882 sq ft)

Disp/length: 173

SA/D Ratio: 18

Engine: 2 x 29hp Yanmar

Transmission: Saildrive

Water: 300L / 79gal (+300L optional)

Fuel: 400L / 103gal

Berths: 6-12

RCD Category: A8

Designer: VPLP

Builder: Beneteau

UK Agent: sea-ventures.co.uk